Noémi Adda – “Look and then draw, and look again and keep on drawing”

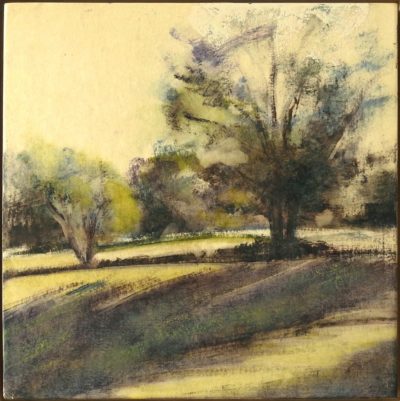

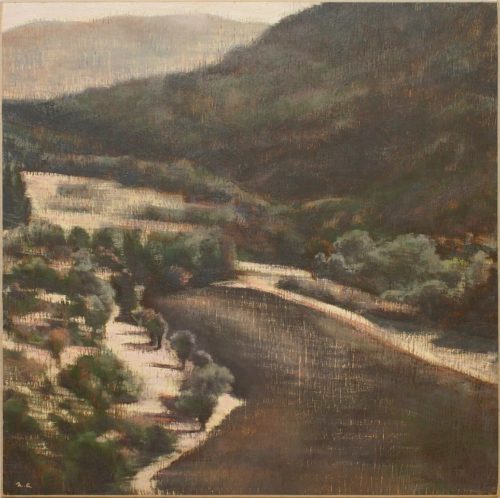

As you wind your way up by car to Truinas the countryside gradually turns into a painting by Noémi Adda. Altitude 650 metres; distance from Dieulefit 8 km and from Montélimar 20km. The traffic on the way is sparse and at places the road narrows leaving barely enough space for cars coming from opposite directions to cautiously cross paths. A barking dog may come rushing out of one of the few old farmsteads and follow the car for a short distance before deciding it is in vain. By and of itself the little village of Truinas is unremarkable, a cluster of houses one of which is occupied by the Mairie that watches over a small community of 130 souls, an old stone catholic church and a protestant church. However, the scenery is beautiful, particularly for a painter like Noémi who likes to work outdoors. Some of the land that has been moulded by man over the course of many centuries for agricultural purposes reaches up the mountain slopes to where nature turns wild. The air is pure and limpid, the light fall ever changing, rapidly when the Mistral chases the clouds across the sky casting shifting shades, slower when the sun passes behind the mountains that spread their shadow over the land at their feet.

As you wind your way up by car to Truinas the countryside gradually turns into a painting by Noémi Adda. Altitude 650 metres; distance from Dieulefit 8 km and from Montélimar 20km. The traffic on the way is sparse and at places the road narrows leaving barely enough space for cars coming from opposite directions to cautiously cross paths. A barking dog may come rushing out of one of the few old farmsteads and follow the car for a short distance before deciding it is in vain. By and of itself the little village of Truinas is unremarkable, a cluster of houses one of which is occupied by the Mairie that watches over a small community of 130 souls, an old stone catholic church and a protestant church. However, the scenery is beautiful, particularly for a painter like Noémi who likes to work outdoors. Some of the land that has been moulded by man over the course of many centuries for agricultural purposes reaches up the mountain slopes to where nature turns wild. The air is pure and limpid, the light fall ever changing, rapidly when the Mistral chases the clouds across the sky casting shifting shades, slower when the sun passes behind the mountains that spread their shadow over the land at their feet.

These are the surroundings where Noémi decided to settle with a view to painting landscapes. Considering how many she has made, the environment has proved to be an unending source of inspiration. A neighbour once remarked “Her landscapes change all the time, they are familiar but never the same, their diversity is astonishing, whereas she never moves far away.” At first sight the landscapes are naturalistic and whoever is familiar with the Drôme will immediately recognise the region in which they were painted. No attempt has been made to deform the subject like the impressionists, expressionists, fauvists or cubists do. Noémi paints exactly what she sees.

They say that what artists create is basically a projection of who they are. I believe it was the American artist Edward Hopper who once stated that when he painted a landscape it was in fact a dialogue he was having with himself. I often wonder whether painters don’t reveal more about themselves in landscapes than in self-portraits for they are less affected by self-consciousness and wishful thinking. Having admired Noémi’s beautiful and arresting landscapes made me want to meet her and find out who she was. We met and we talked, and this is what she told me.

They say that what artists create is basically a projection of who they are. I believe it was the American artist Edward Hopper who once stated that when he painted a landscape it was in fact a dialogue he was having with himself. I often wonder whether painters don’t reveal more about themselves in landscapes than in self-portraits for they are less affected by self-consciousness and wishful thinking. Having admired Noémi’s beautiful and arresting landscapes made me want to meet her and find out who she was. We met and we talked, and this is what she told me.

You work alternately in Paris which is a throbbing metropolis and in the quiet and peaceful surroundings of Truinas in the Drôme. I could imagine that the atmosphere being completely different this could affect the kind of work you make. The environments are different, you breathe a different kind of air, speak with people who have different concerns, come across new faces and more generally adapt to another lifestyle. It stands to reason that Truinas is the place where you paint landscapes but what do you make in Paris? Working out of doors like you do in the Drôme is not an option and I don’t expect you cart your canvases around from one place to another.

Yes, that is quite true and the only things I do take along with me when I go back to Paris come from my vegetable garden! But, more to the point! I paint the same subjects and I observe nature and if I wish I can also draw out of doors for I live at the edge of the Bois de Vincennes. The difference between Truinas and Paris is that in Paris I have less space and as a result the format of my paintings is smaller. Of itself as far as I am concerned the subject doesn’t count most but what is important is how to express my feelings with regard to nature. To this end I try out various techniques such as monotype, sgraffito, drawing, oil pastels.

The landscapes you make of the Drôme are remarkably true to nature. They are not however precise renditions of a specific site but they express what you feel when you have a particular landscape before you. How do you manage to make these landscapes of the Drôme seem so real and recognisable?

The landscapes you make of the Drôme are remarkably true to nature. They are not however precise renditions of a specific site but they express what you feel when you have a particular landscape before you. How do you manage to make these landscapes of the Drôme seem so real and recognisable?

The reason is perhaps that I don’t seek to deform what I see. I simply trust my vision and the emotion it gives rise to. And, when the emotion is overwhelming I feel an urgent need to express and share it through a painting.

You started to earn a living at a very young age. Was your work in any manner related to art? And, by the way did you already draw and paint as a child?

My job was not directly connected to art although I was involved in book publishing making mock-ups, which is an activity that involves creativity. Like most children I loved to draw and to paint …but since then I’m afraid I have lost my innocence, in other words a certain candour and spontaneity!

If I have got it right you showed your work for the first time in Paris. After that the gallery Artenostrum in Dieulefit discovered your paintings and decided to back you. As a result, they organise exhibitions of your work on a regular basis. You have also exhibited in Tours, Besançon and in the Ardèche.

Yes it is true that Artenostrum was a great help for they opened up an opportunity to give significance to my work notably by sharing it with others and submitting it to their appreciation which eventually led some of them wanting to own a painting and to buy it.

You are a self-taught artist. I suppose that here and there you attended courses, studied the work of other painters and experimented using different techniques. I remember looking at one of your paintings some years ago and how it reminded me of a landscape painting by Balthus. There was also something about it that reminded me of Corot, a form of sobriety! Can you name a few painters you admire and who inspire you?

There are painters I envy. I have studied Balthus’s landscapes a lot. In Paris a close friend of my family was a painter. I was bewitched by his paintings that I often went to see in his studio. I also observed how he worked while I posed for him. When he painted there was a look of extreme intensity in his eyes as though he wanted nothing to escape his notice. He acted like someone possessed. He used to tell me that if I wanted to become a painter I had to learn to look and then draw and look again and keep on drawing. He was right. His wife was also a painter and we both posed for him one after the other. It was a crucial period for me. I never attended an art school, so I had to find out for myself which is perhaps a slower process but an enriching one because the personal commitment is greater. It also proved to be a test of endurance!

When I see a landscape by Corot it moves me very much. Great painters intimidate me but at the same time they whet my appetite. At the end of his life Cézanne painted the Sainte-Victoire Mountain over and over again, something I consider to be a fine example of the renewal and transfiguration of reality. The watercolours he made during this period are vibrant with life!

Among the paintings you have put online – the early ones – there are still-lifes, paintings of trees that quite obviously hold a fascination for you, one of a dog and another of a sheep but no human being. Yet many of your landscapes testify to human presence if only because parts have been altered for agricultural purposes. The human face and figure don’t seem to interest you!

On the contrary, they interest me very much. For many years I posed as a model for my ex-husband who was a sculptor. He was never satisfied while he worked whereas I found his sculptures very beautiful. I shared the difficulty he had of freeing himself from resemblance. When I started to paint, I felt the urge to make portraits and for a long time I painted self-portraits which proved to be a very useful exercise. I often draw people who are close to me and when I do these are always moments of great intensity that are dear to me. You are right about there never being a human figure in my landscapes, and I have often been asked why. The reason is perhaps that it is my way of imagining the same mountains, the same trees, the same light fall and shadows long ago, in the dawn of time.

Can you briefly describe the appeal of painting out in nature?

I am a contemplative and solitary person and working out of doors is a form of meditation. It doesn’t take long before I become invisible to my surroundings; I am then free to observe what is happening around me without disturbing anyone; even animals are not bothered by my presence and sometimes they will come up close to where I am. This is when I feel good about myself, in the right place and at ease, and I can begin to paint. Miro used to say: “When I start to paint a landscape, I begin by a feeling of deep affection for it and it is out of this love that a slow understanding of the place will develop.”

What is the special charm of Truinas and its surroundings that made you want to live and work here?

What is the special charm of Truinas and its surroundings that made you want to live and work here?

When I came to Truinas for the first time I said to myself: this is clearly and without the shadow of a doubt the place where it is imperative that I should paint.

Posted in: Art